The Factory was sold in 1994 to Robert Brattii

From the ASSOCIATED PRESS

CUMBERLAND, Md.—Before buying the struggling Cumberland Macaroni Co. four years ago, Robert Bratti’s only hands-on experience with pasta was eating it.

He renamed the company Cumberland Pasta Co. and tripled its output to about 7 million pounds in the past year. Bratti hopes to reach 15 million pounds a year by 2000.

“For me, nothing is impossible,” said the irrepressible Canadian.

Bratti, 61, models his can-do attitude on Napoleon’s, but takes business advice from his wife, Marjorie, formerly product manager for Borden Inc.’s Canadian pasta division and now Cumberland Pasta’s vice president for marketing.

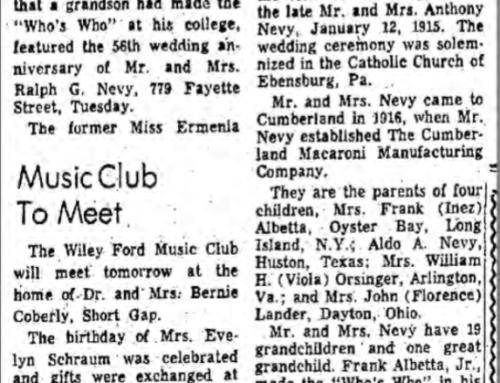

Together, they have reshaped the 93-year-old firm by shifting its focus from the consumer market to bulk buyers such as the military, state prisons and public universities.

The bright blue Cumberland Alpine Eagle label, a longtime fixture on area supermarket shelves, is virtually gone, along with the retail trade that now makes up just 5 percent of the firm’s sales.

Its new brands, American Eagle and Marco Polo, are sold in 10- and 20-pound boxes to institutions and restaurants.

“We just didn’t have the equipment for retail. If we had had retail packaging equipment here, we would have been aggressively pursuing the retail market or private labels. What was available to us was the ability to produce in bulk economically,” Bratti said.

The company’s strategy is sound in today’s pasta market, where most of the growth is in bulk sales, according to Josh Sosland, executive editor of Milling & Baking News in Kansas City, Mo.

“I think the pasta business is one that has been very friendly to niche players,” Sosland said. “When you’re talking bulk, you’re talking about a market that doesn’t have dominant brands.”

The strongest companies in the U.S. industry, which makes more than 2.6 billion pounds of pasta annually, are bulk producers American Italian Pasta Co. of Excelsior Springs, Mo., and Dakota Growers Pasta Co., a wheat-farmer cooperative in Carrington, N.D., Sosland said.

Retail leader Borden, maker of the Prince and Creamette brands, has closed or sold at least five pasta plants in recent years. And Hershey Foods Corp. said in November it was considering selling its U.S. pasta business.

People are still eating pasta, but more of them are buying it in five-pound bags from wholesale clubs, Sosland said.

“The retail demand for pasta, particularly at supermarkets, is flat to slightly declining,” he said.

The change has been good for Cumberland, a shrinking Appalachian city with easy interstate highway access. Bratti said he employs 45 people full time, up from 12 part-timers when he bought the red brick plant for $500,000, including a $200,000 state loan. He spent another $200,000 repairing the building and updating the operations.

“I had to learn the business from scratch,” said Bratti, whose former business, a family-owned mechanical contracting firm in Toronto, closed during the economic recession of the late 1980s and early 90s. “I made some mistakes but I eventually learned, and after four years, I know what I’m doing in the pasta business.”

Machines on the plant’s upper floor mix flour and water, then extrude the bready-smelling paste in three dozen shapes, from spaghetti and lasagna — “long goods” in trade parlance—to shells, penne and elbows.

Fresh pasta rolls steadily from the machines into dryers, the short goods by conveyors, the long goods by workers who carry 20-inch strands of spaghetti and lasagna noodles draped over 4 1/2 -foot wooden poles.

Bratti, who plans to become a U.S. citizen, said he supplies pasta to public institutions in eight states and to the U.S. Navy. He also offers kosher products under the Ben David’s label, and he is developing an upscale brand, Casa di Bratti, for fine restaurants.

“Pasta is healthful, economical and nutritious,” he said. “Regardless of what happens economically with the nation, the bottom line is, you’ll always be eating pasta.”

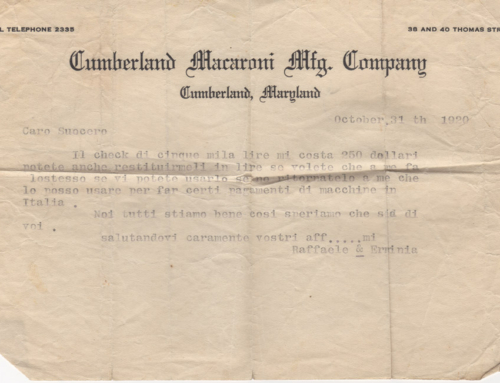

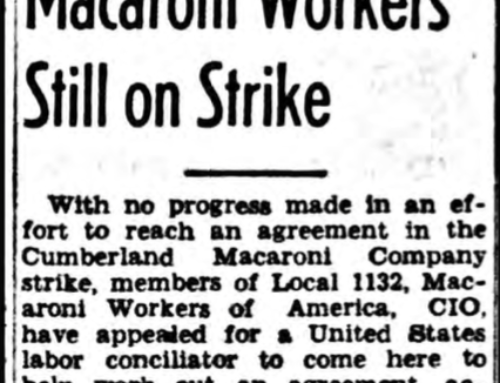

The letter below is a response to a letter Barbara Orsinger Adolfson wrote to congratulate Robert Bratti, the new owner of the pasta factory.

![]()

May 1, 1995

Mrs.Barbara Orsinger Adolfson

Madame:

It was with extreme pleasure to have received your letter. You are the only one of the family that has approached me other than on a business basis, to inquire about the status of the business and the prospects of the future. Your sentimentality was touching.

The “grand old lady of Thomas Street” had practically reached a state of total collapse due to neglect, lack of interest and abuse.

It is believed that my arrival was timely to stop any future deterioration and in the past 9 months, I have finally reestablished the business into a state of being operable again. It has been the most difficult project I have ever undertaken. I utilized every bit of entrepreneurial experience I had and incorporated every managerial skill I had at my disposition plus a few new ones to accomplish this feat. We are not breaking even yet, but we are improving every month.

Together with our new plant manager, we are restoring the integrity of the building and improving our manufacturing process and quality. With the installation of a computer network, fax machines, etc., our modernized offices have become much more efficient. Our new sales manager and I are now in the process of acquiring and establishing new markets.

I am very excited about our prospects here and with hard work and some luck we will reestablish the “Grand old lady of Thomas Street” into a vibrant, profitable company, the status that it deserves in Cumberland. I would be honored, together with my wife, to have you and your family visit our plant at your convenience. The doors are always open to you. If you could give me more information on the brothers and their offspring, a family tree so-to-speak, I would appreciate it.

This letter will be attached to a case of #9 with our compliments. I hope to meet you and your family soon.

Sincerest Regards,

Robert A. Bratti

President

Cumberland Pasta Company Incorporated