Pasta manufacturing is both science and art. Let’s start our plant tour outside on the loading dock where trucks or railroad cars deliver the coarse semolina flour that has been milled from durum wheat. A special vacuum hose pulls the wheat flour inside the plant and places it in gigantic bins. Small plant purchase the wheat flour in huge bags.

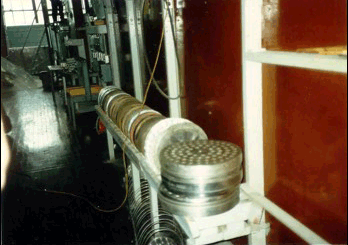

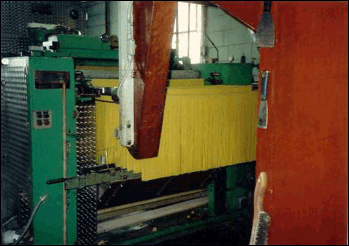

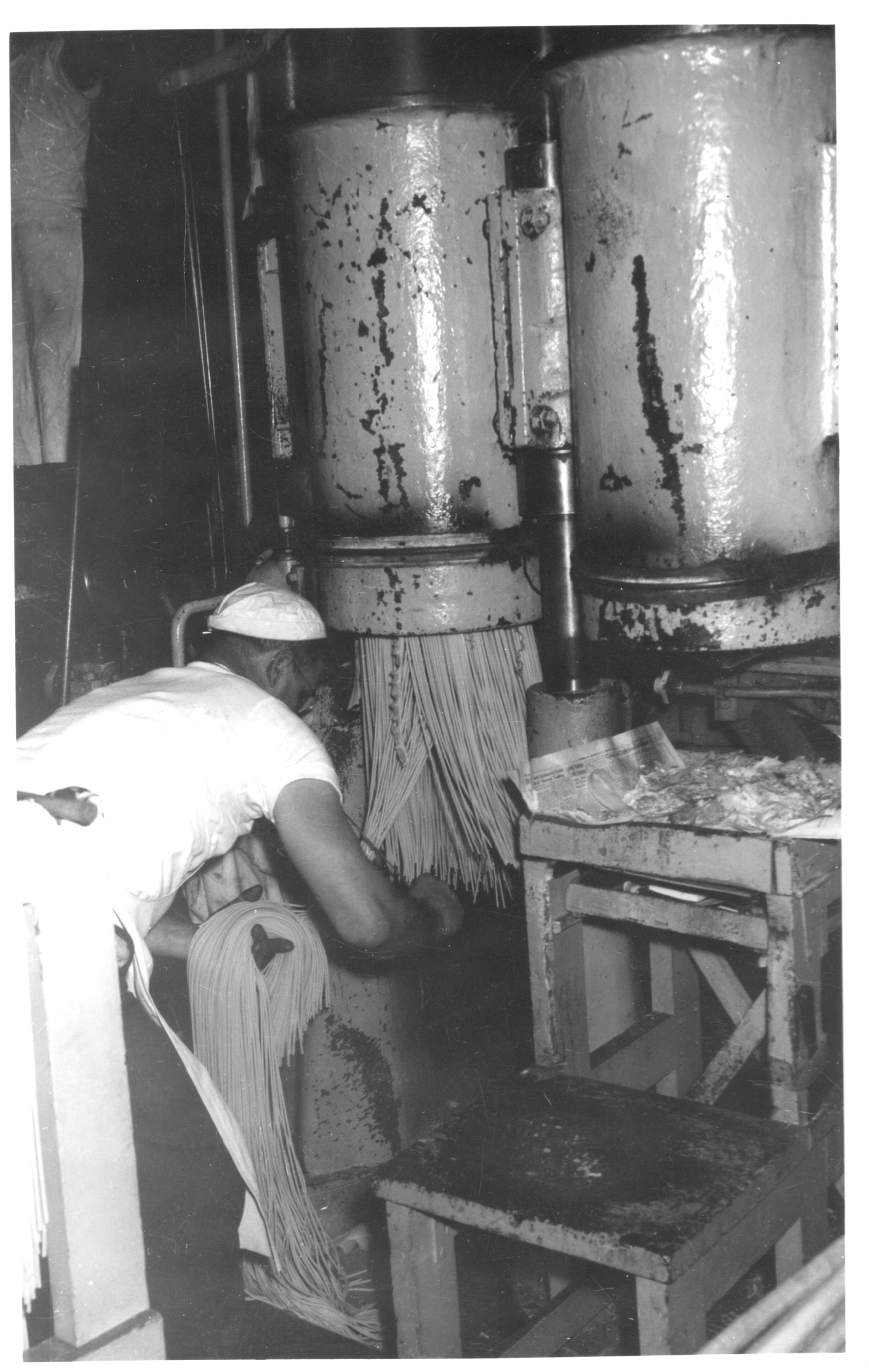

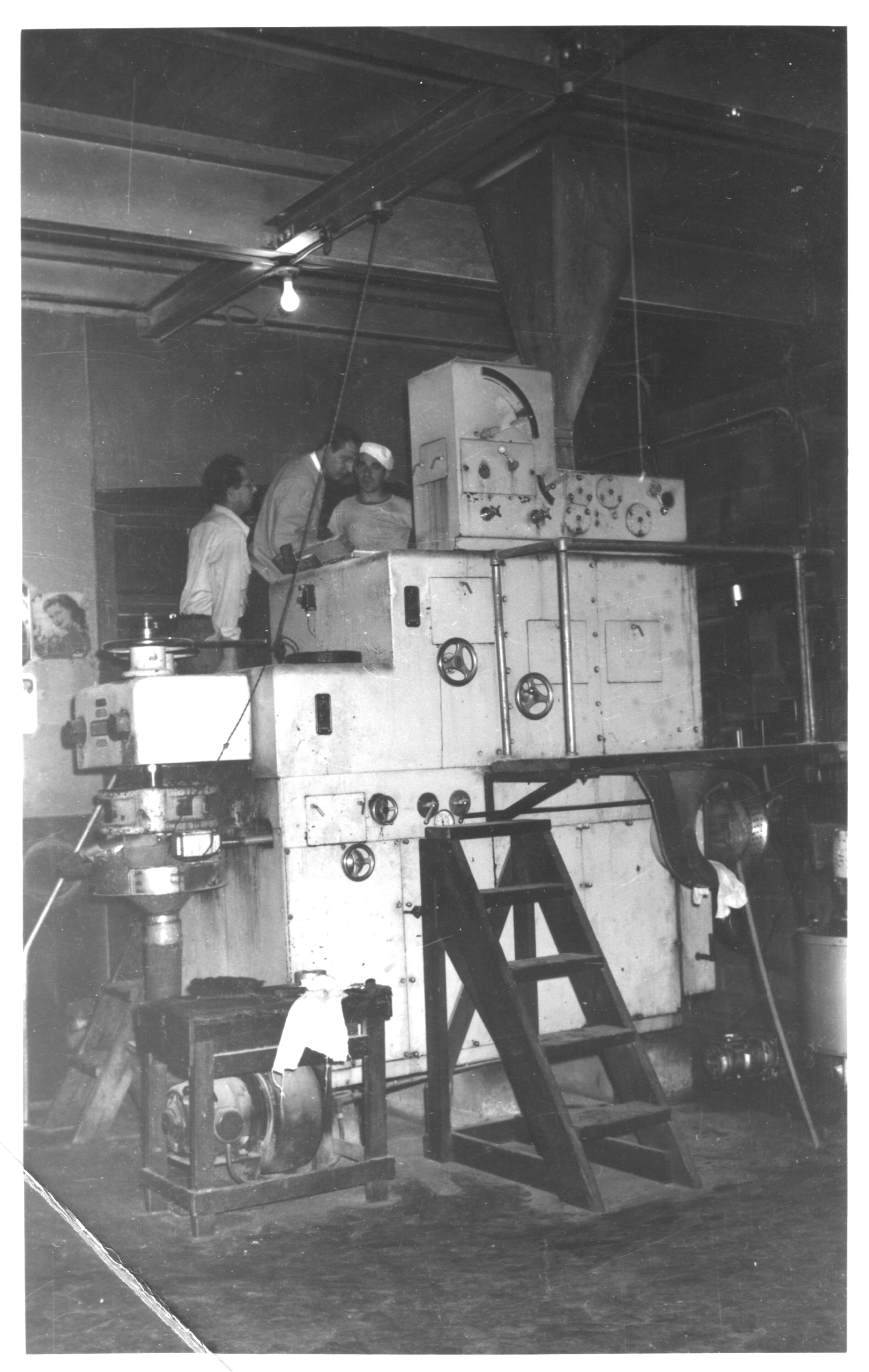

Let’s step inside and follow the semolina to see how it becomes pasta. You won’t need a jacket because the temperature in a pasta plant can sometimes be as high as 100 degrees! (You will find out why later.) Under carefully controlled conditions, the wheat flour is mixed with water under vacuum in a huge industrial mixer to form a tough dough. For some products, eggs and natural flavorings, such as spinach and tomato powders, are added at this time. Once it has reached the perfect consistency, the dough is ready for shaping. Most pasta shapes result when the dough is force or “extruded” through “dies,” large metal discs full of holes. Since these dies can weigh from 300 to 350 pounds each, special cranes or carts are needed to hoist them pasta being cut into position. The size and shape of the holes in these dies determines what the finished pasta shape will be. Round or oval holes produce solid rods, such as vermicelli and spaghetti. When a steel pin is placed in the center of each hole in the die, the dough comes out in hollow rods, such as macaroni. To give macaroni its curved shape, the pin has a notch in one side. This allows the dough to pass through more quickly on one side, causing it to curve before it is cut to size with a revolving knife.

Other pasta shapes are cut out of flat sheets of dough, such as noodles or bow ties. In fact, bow ties are one of the most difficult shapes to make, according to one expert U.S. pasta manufacturer. This is because they are “stamped” out of the dough while simultaneously being crimped in the middle to create the bow shape. The dough must be neither too moist nor too dry or the bows will turn out lopsided.

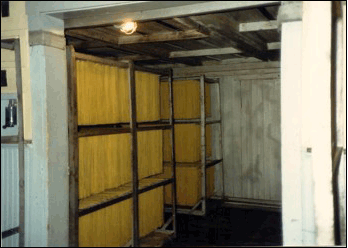

Once the pasta is extruded, it is cut to the proper length and then begins its trip through the drying process. The machines that dry pasta can be up to 320 feet long – about as long as a football field. (This is why you don’t need that jacket!) Drying is one of the most critical steps to achieving a perfect finished product. If the pasta is dried too quickly, it will break easily. If dried too slowly, it could spoil. Inside the dryers, the pasta is subjected to constantly circulating, very hot, moist air. Not surprisingly, different pasta shapes require different drying times according to their thickness. Today’s high tech machines have come a long way from the early part of this century when pasta was hung on racks to dry outdoors in the sun. Then, a stretch of damp or rainy weather could seriously hamper a pasta maker’s business!

The finished product is shuttled off to the plant’s packaging area. Here, dexterous machines open brightly colored boxes which march by like toy soldiers to be filled and sealed. Other pasta shapes such as noodles whiz through a form-fill-and-seal machine which automatically creates a clear bag from a sheet of cellophane, drops in just the right amount of pasta, then seals it on its way to large shipping boxes. You might also see such delicate pasta specialty shapes as lasagne being packaged by hand to protect it from breakage. The best part of any pasta tour, of course, is the trip to your own kitchen.